METAPHYSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NATURE IN THE FINE ARTS

METAFIZYCZNE INTERPRETACJE PRZYRODY W SZTUKACH PIĘKNYCH

According

to Aristotle, everything that lives has a soul - plants have vegetative

souls, animals have sensual souls and people - thinking souls. According

to that view, the living world has two aspects: material and spiritual.

Such awareness has existed in the European culture since the antiquity.

According to it, the Europeans also expressed their feelings to the

natural world in the fine arts. Thus the title of this document:

Metaphysical interpretations of nature in the fine arts. To show the

sources and permanency of the belief of contemporary inhabitants of

Europe and their ancestors in the dual - material and spiritual -

dimension of nature, my lecture will be of a historical, even

chronological nature.

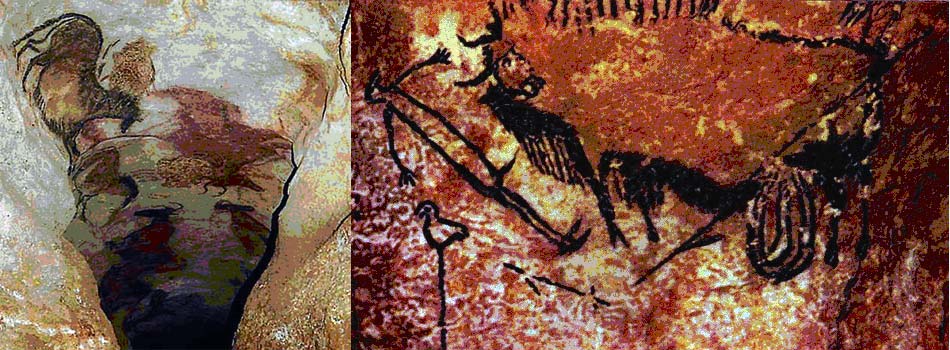

The oldest artist who left traces of his activities in the artistic

world is a Paleolithic hunter. He was the author of wonderful frescos

covering the walls of caves. Figure 1 shows paintings from a French cave

in the Lascaux and a Spanish one in Altamira. They present physical

images of animals but their location and arrangement prove that they

also had a metaphysical meaning in the sanctuary of the cave. Together,

they formed a spiritual world parallel to the material world. It

constituted the reverse of an allegory of the Plato cave where shadows

on walls defined the material world. The meaning of a cave as a

sanctuary was thus described by religion expert Mircea Eliade: A cave

depicts the other world but also the entire Universe. (...) A ritual

cave sometimes imitates the sky at night. In other words, it is the

imago mundi. The universe in miniature1.

We eat your bodies, but we don't know

how to eat your souls.

Według Arystotelesa wszystko, co żyje jest obdarzone duszą - rośliny posiadają duszę wegetatywną, zwierzęta zmysłową, a ludzie rozumną. Zgodnie z tym poglądem świat żywy posiada dwa aspekty: materialny i duchowy. Świadomość tego istniała w kulturze europejskiej od czasów antycznych. Tak też Eropejczycy wyrażali swoje odczucia wobec świata przyrody w sztukach pięknych. Stąd tytuł tego opracowania: Metafizyczne interpretacje przyrody w sztukach pięknych. Aby pokazać źródła i trwałość przekonania dzisiejszych mieszkańców Europy i ich przodków o dwoistym – materialnym i duchowym wymiarze przyrody, mój wywód będzie mieć historyczny, wręcz chronologiczny, charakter.

Najstarszy z artystów, który pozostawił ślady swoich działań w świecie sztuki, to paleolityczny myśliwy. Był on twórcą wspaniałych fresków pokrywających ściany jaskiń. Na rysunku 1. widzimy malowidła z francuskiej jaskini w Lascaux i z hiszpańskiej w Altamirze.Widnieją na nich fizyczne wizerunki zwierząt, ale ich usytuowanie i skomponowanie świadczy o tym, że posiadały także metafizyczne znaczenie w sanktuarium jaskini. Razem tworzyły duchowy świat, równoległy do świata materialnego. Stanowił on odwrotność do alegorii platopńskiej jaskini, w której cienie na ścianach określały świat materialny. Znaczenie jaskini jako sanktuarium tak określa religioznawca Mircea Eliade: Grota zaś wyobraża tamten świat, ale również cały Wszechświat./.../ Grota rytualna naśladuje niekiedy nocne niebo. Innymi słowy jest ona imago mundi. Wszechświatem w miniaturze1.

Jemy wasze ciała, ale nie wiemy

jak zjeść wasze dusze

Fig. 1. Entrance to the sanctuary in Lascaux, an aurochs and man in the sanctuary in Altamira

Rysunek 1. Wejście do sanktuarium w Lascaux, oraz żubr i człowiek w sanktuarium w Altamirze.

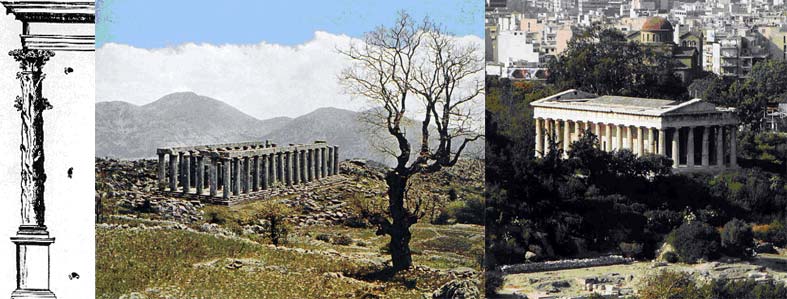

The antiquity period is nearly contemporary for us in comparison with the Paleolithic. The Greek merchant, breeder and farmer created works we have been emulating to this day and wrote dramas staged in theaters to this day. As an animal was the sign defining the natural world for the Paleolithic hunter a tree was such a sign for the farmer. The Greeks worshipped their gods not only in underground caves but also, as all Indo-Europeans, in forests. Thus their most important sanctuaries are surrounded by a symbolic forest of columns. Once the megaron, the primary house with a vestibule supported by two trunks - described in the Iliad and Odyssey - now acquired the rank of a God's cave, a sanctuary sur¬rounded by a forest of columns. Marble columns visible in Figure 2 acquire the intermediate being related to the rock of which the shrine was built and to the living tissue of the holy grove surrounding it. Man looks at the sanctuary from beyond but is also a part of it.

A column casts a shadow like a tree

in this shadow gods speak

about the life of immortals.

Starożytność antyczna to, wobec paleolitu, czasy niemal nam współczesne. Grecki kupiec, hodowca i rolnik tworzyli dzieła, które do dzisiaj naśladujemy i pisali dramaty, które do dzisiaj są wystawiane w teatrach. Tak, jak dla paleolitycznego myśliwego znakiem określającym świat przyrody było zwierzę, dla rolnika takim znakiem było drzewo. Grecy swoich bogów nie czcili tylko w podziemnych grotach, ale jak wszyscy Indoeropejczycy w lasach. Stąd ich najważniejsze sanktuaria są otoczone symbolicznym lasem kolumn. Kiedyś megaron, pierwotny, opisywany w Iliadzie i Odysej dom z przedsionkiem podpartym dwoma pniami, teraz uzyskał rangę boskiej groty, sanktuarium otoczonego lasem kolumn. Widoczne na rysunku 2. marmurowe kolumny przyjmują pośredni byt spokrewniony zarówno ze skałą, z której jest zbudowana świątynia, jak z żywą tkanką otaczającego ją świętego gaju. Człowiek patrzy na sanktuarium z zewnątrz, ale jest też jego częścią.

Kolumna rzuca cień jak drzewo

w tym cieniu rozmawiają bogowie

o życiu nieśmiertelnych

Fig. 2. The classical column as a tree trunk, illustration in Philibert de l’Orme's Le Premier Tome de l'Architecture, 1567. Shrines: of Apollo Epikurios in Bassaia and of Hephaestus (erroneously called the Theseion) - Athenian agora.

Rysunek 2. Klasyczna kolumna jako pień drzewa ilustracja do Philibert de l'Orme's Le Premier Tome de l'Architecture, 1567. Świątynie: Apollina Epikuriosa w Bassai i Hefajstosa (zwana błędnie Tezeionem) - agora ateńska

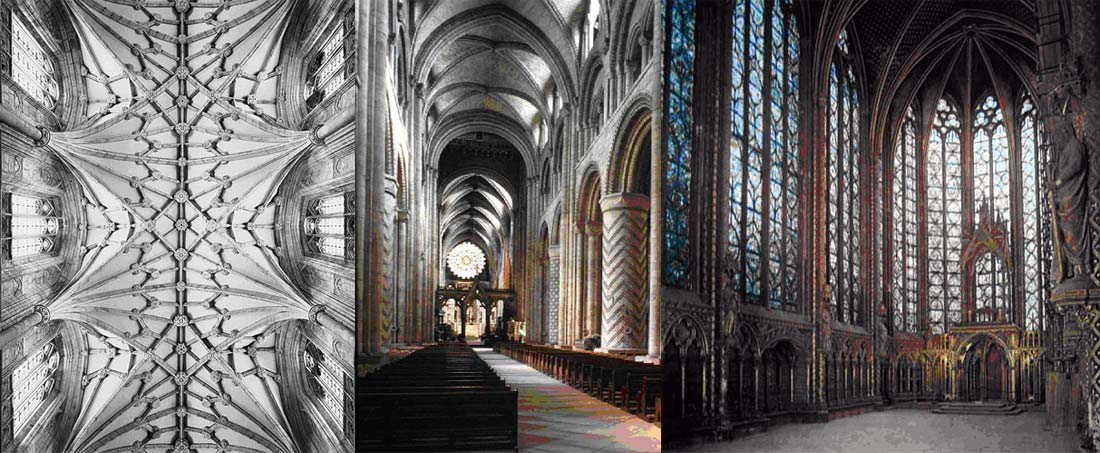

The Christian Middle Ages including superficially christened Indo-Europeans on the north with their archaic cult of trees also see the God through their trunks. In the antique Greece, believers stood outside the shrine; now, they enter its interior. The interior of a cathedral, as we can see on Figure 3, is as the interior of a forest where trunks replace columns and branches on treetops replace the ribbing of vaults. The route of the faithful leads to the sanctuary in the presbytery with the mystic body of the Christ through the forest of columns supporting the vault with stars painted on them showing that this is a vaulting we perceive over the tree tops. Man passing the naves meets the transept, which includes not only the arms of the cross in the scheme of a shrine but also the crossroads within it.

In a forest you can get lost

in a cathedral the light shows us the way

to Jerusalem.

Chrześcijańskie średniowiecze, na północy obejmujące powierzchownie schrystianizowanych indoeuropejczyków z ich archaicznym kultem drzew, także widzi Boga poprzez ich pnie. W antycznej Grecji wyznawcy stali na zewnątrz świątyni, teraz wchodzą do jej wnętrza. Wnętrze katedry, co widzimy na rysunku 3. jest jak wnętrze lasu, w którym pnie zastępują kolumny, a konary koron żebrowanie sklepień. Droga wiernych wiedzie do sanktuarium w prezbiterium z mistycznym ciałem Chrystusa przez las kolumn podtrzymujących sklepienie, na których namalowane gwiazdy wskazują, że jest to sklepienie, które dostrzegamy ponad koronami drzew. Człowiek idąc nawami napotyka transept, który jest nie tylko ramionami krzyża w rysunku świątyni, ale także wewnątrz niej rozstajem dróg.

W lesie można się zagubić

w katedrze światło prowadzi nas drogą

do Jerusalem

Fig. 3. Vault of the cathedral. 1133 Durham. Main nave. "Sainte - Chapelle" in Paris erected to house the crown of thorns relic. 1243-1248

Rysunek 3. Sklepienie katedry. 1133 Durham. Nawa Główna. Sainte - Chapelle w Paryżu wzniesiona dla pomieszczenia relikwii korony cierniowej. 1243-48

As we can see on Figure 4, a tree is not only a symbolic sign of the place where the spirit manifests itself. It is also - or, perhaps, in particular - an archetype, as described by C.G. Jung - a being to which all people in various places and at various times ascribed a similar meaning. It is a sign via which people communicate beyond time and beyond space. An archetype is a place, paradise, the tree of life between heaven and earth. We use an archetype if we want to talk to all people despite their confusion of languages. It was so on April 8, 2005. The coffin with pope John Paul II was laid on a carpet of the type illustrating the paradise. The coffin was made of two layers - the internal one made of wood traditionally considered the material of the Holy Cross in the Eastern tradition, and the external one made of wood used for the cross according to the Western tradition.

Jung was no longer a young man

when he discovered older things

and even the oldest.

Na rysunku 4 możemy zobaczyć, że drzewo jest nie tylko symbolicznym znakiem miejsca, w którym przejawia się duch. Jest także, a może przede wszystkim, archetypem - jak określił to C. G. Jung - bytem, któremu wszyscy ludzie, w różnych miejscach i o różnym czasie przypisywali podobne znaczenie. Jest znakiem, którym ludzie porozumiewają się poza czasem i poza przestrzenią. Archetypem jest miejsce, raj, drzewo życia pomiędzy niebem i ziemią. Posługujemy się archetypem, jeżeli chcemy przemówić do wszystkich ludzi mimo ich pomieszania języków. Tak było 8 kwietnia 2005 roku. Trumna z papieżem Janem Pawłem II została złożona na dywanie typu przedstawiającego raj. Trumna była dwuwarstwowa - wewnętrzna z drewna tradycyjnie uznawanego za materiał Krzyża św. w tradycji wschodniej, zewnętrzna w drewna, z którego wykonano krzyż według tradycji zachodniej.

Jung nie był już młody,

kiedy odkrył rzeczy starsze,

a nawet najstarsze

Fig. 4. The Tree of the Soul. William Law 1764-1781: The Works of Jacob Behmen, London. The Tree of Life. Soumak carpet, Caucasus, 18th c. The funeral of John Paul II

Rysunek 4. Drzewo symbolizujące duszę ludzką. William Law 1764-81: The Works of Jacob Behmen, London. Drzewo życia. Sumak, Kaukaz 18 wiek. Pogrzeb Jana Pawła II.

Contemporary European arts no longer refer to Aristotle; they refer to Plato. They do not refer to unit things and souls of which they assemble the world but to the world as a comprehensive existence. The visible world is a coating that imperfectly reflects the ideal world (Plato's cave mentioned earlier, in which our world is a shadow on the cave wall, imperfectly reflecting beings illuminated by fire). An ideal landscape to which, as to a model, the real landscape should proceed is an image of the harmony of culture and nature. We can see that on Figure 5. Art should strive to reflect the model landscape and omit its imperfect visible form. The pastoral landscape full of joy and light seemed to reflect ancient fictitious Arcadia and the Temple valley; it was associated with the concept of the "gentle Primitivism"2 so dear to the philosophers of the Enlightenment. One of the creators of an ideal landscape, Nicolas Poussin, even created a theory of painting modes, according to which each topic requires a separate approach with its mood adapted to the content3.

Only a shadow of higher existence reaches the earth.

Europejska sztuka nowożytna odwołuje się już nie do Arystotelesa, ale do Platona. Nie odwołuje się do rzeczy i dusz jednostkowych, z których składa świat, ale do świata jako całościowego bytu. Świat widzialny jest powłoką w niedoskonały sposób oddającą świat idealny (wspomniana wcześniej platońska jaskinia, w której nasz świat jest cieniem na ścianie jaskini w sposób niedoskonały oddającym oświetlone ogniem byty). Pejzaż idealny, do którego, jako do wzoru, powinien zmierzać pejzaż realny, jest obrazem harmonii kultury i natury. Widzimy to na rysunku 5. Sztuka powinna dążyć do oddania wzoru pejzażu, a pomijać jego niedoskonałą, widoczną formę. Radosny i pełen światła pejzaż pastoralny zdawał się być odwzorowany na starożytnych fikcjach Arkadii i doliny Temple; kojarzył się z tak drogą oświeceniowym filozofom koncepcją "łagodnego Prymitywizm”2. Jeden z twórców pejzażu idealnego, Nicolas Poussin stworzył nawet teorię modusów malarskich, według której każdy temat wymaga odrębnego ujęcia, dostosowanego nastrojem do treści3.

Do ziemi dociera tyko cień bytów wyższych

Fig. 5. Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia ego, 1640. Claude Lorrain The Expulsion of Hagar, 1668, Oil on canvas, 107 x 140 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Rysunek 9. Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia ego. Claude Lorrain Odesłanie Hagar, 1668, olej, płótno, 107 x 140 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

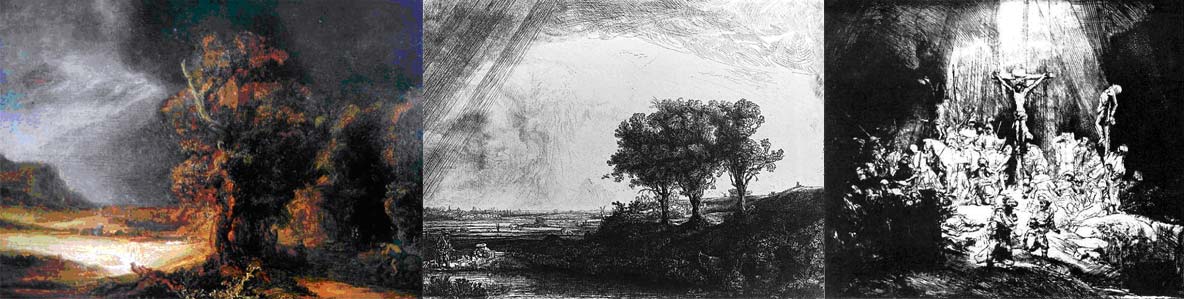

The religious division of Europe developed the religious dimension of a presented landscape. The Reformation returned to the prohibition to personify God in His images. In the arts of the Reformed countries, the landscape exists as a substitute of a religious image - a background for the descent of God and sanctified through His presence. Its liturgical meaning manifests itself in the presence of archetypes and toposes (cultural signs). We can see that in works by Rembrandt on Figure 6. The tree, water and a stone bridge as a selected place. Three trees as the Golgotha.

Elements of earth, air, water and human

create places of God's presence.

Podział religijny Europy rozwinął religijny wymiar odwzorowywanego pejzażu. Reformacja powróciła do zakazu personifikacji Boga w jego wizerunkach. W sztuce krajów zreformowanych pejzaż występuje jako substytut obrazu religijnego - tło zstąpienia Boga i przez jego obecność uświęcone. Jego liturgiczny sens przejawia się poprzez obecność w nim archetypów i toposów (znaków kulturowych). Widzimy to w dziełach Rembrandta na rysunku 6. Drzewo, woda i kamienny most jako miejsce wybrane. Trzy drzewa jako Golgota.

Żywioły ziemi, powietrza, wody i człowieka

tworzą miejsca bożej obecności

Fig. 6. Rembrandt, Good Samaritan. Landscape with three trees, 1643, etching. Rembrandt, Three crosses, 1653, etching

Rysunek 6. Rembrandt, Miłosierny Samarytanin. Pejzaż z trzema drzewami, 1643, akwaforta. Rembrandt, Trzy krzyże, 1653, akwaforta,

The Romanticism went even further. Caspar David Friedrich, the son of a pastor, used landscape paintings we can see on Figure 7. to talk about God. The rock and the fir tree are symbols of unyielding faith. (...) Fir trees around the cross symbolize hope set by man on Christ4. The fundamental principle adopted by the artist was to consider natural phenomena the proof of existence of the Absolute - a pantheistic belief that each natural phenomenon has a soul5.

Mountains and trees lead to God,

who is in heaven.

Romantyzm poszedł jeszcze dalej. Casparowi Davidowi Friedrichowi, synowi pastora, malarstwo pejzażowe, które możemy zobaczyć na rysunku 7. służyło do rozmowy o Bogu. Skała i jodła to dwa symbole niewzruszonej wiary. /.../ Jodły wokół krzyża symbolizują nadzieję pokładaną przez człowieka w Chrystusie4. Fundamentalną zasadą przyjętą przez artystę było uznanie zjawisk przyrody jako dowodu na istnienie Absolutu - panteistycznego przekonania, że każde przyrodnicze zjawisko posiada duszę.5

Góry i strzeliste drzewa dążą do Boga,

który jest w niebie

Fig. 7. Caspar David Friedrich. Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar) 1808. Oil on canvas. 115 x 110 cm Gemaldegalerie, Dresden. The Cross In the Mountains 1812. Oil on canvas, 45 x 37 cm Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf

Rysunek 7. Caspar David Friedrich. Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar) 1808 Oil on canvas, 115 x 110 cm Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. The Cross in the Mountains 1812 Oil on canvas, 45 x 37 cm Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf

Romanticism penetrated by individualism transformed the meaning of

nature as a place where God's presence manifests itself to the place of

con¬versation with God. It also led to the more secularized concept of

nature manifesting itself through a landscape, which reflects man's

moods. As Charles Baudelaire wrote in his famous Correspondences6:

Nature is a temple in which living pillars

Sometimes give voice to confused words;

Man passes there through forests of symbols

Which look at him with understanding eyes.

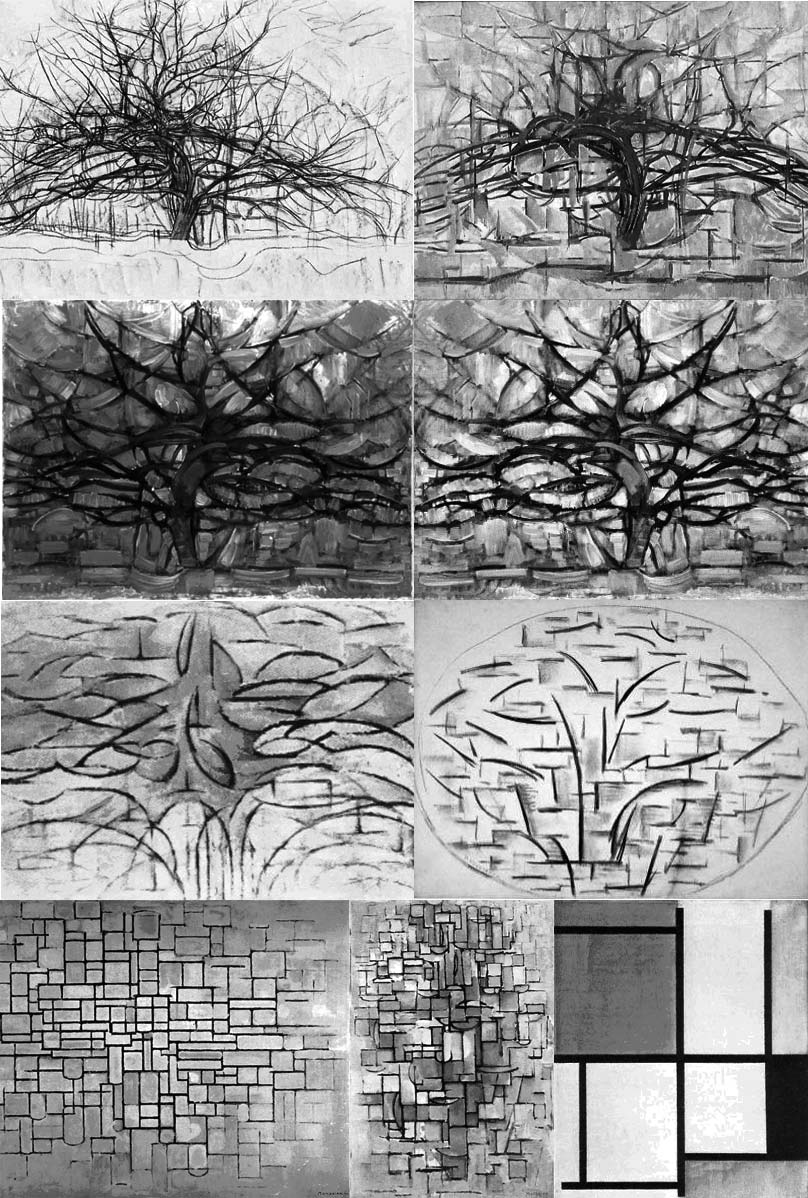

Modernism and the 20th century departed from mimicry as the principle of creation. Nature constitutes the basis for rational abstract arts through the abstracting of structure from it. Through the analysis of a form of a living organism we can read its structure. Members of the Dutch De Stijl group were the most orthodox ones in their treatment of the abstract art. As Paul Owery wrote: All Dutch members of De Stijl came from Calvinist families. The first commandment: "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image..." was interpreted literally. De Stijl transformed the religious prohibition banning the engraving of images into an esthetic prohibition7. Recognized nature will make independent creation of future mechanisms possible. As Mondrian wrote in De Stijl: In the future, man will choose his own surroundings and will create them by himself. Because of that, he will not feel the lack of nature as, in the past, the people forced to abandon ii did (...) Man will build hygienic and beautiful cities thanks to the sustained contrasting of buildings, structures and open space. Then, he will be as happy at home as beyond it8. As an example, Figure 8 presents the structure of an abstract arrangement prepared by Mondrian in a series of paintings, based on the apple tree.

Branches of an abstract tree

are like orthogonal streets.

Przesiąknięty indywidualizmem romantyzm rozwinął sens natury, jako miejsca przejawiania się boskiej obecności w pojęcie natury, jako miejsca rozmowy z Bogiem. To także prowadziło do bardziej zsekularyzowanego pojęcia przejawiającej się poprzez pejzaż natury, która oddaje nastrój człowieka. Jak pisał Charle Baudelaire w słynnym sonecie Correspondences6:

Natura jest świątynią, kędy słupy żywe

Niepojęte nam słowa wymawiają czasem.

Człowiek śród nich przechodzi jak symbolów lasem,

One mu zaś spojrzenia rzucają życzliwe.

Modernizm i XX wiek odszedł od mimetyzmu, jako zasady tworzenia. Przyroda, poprzez abstrahowanie z niej konstrukcji stanowi podstawę racjonalnej sztuki abstrakcyjnej. Możemy poprzez analizę formy żywego organizmu odczytać cechującą go konstrukcję. Najbardziej ortodoksyjnie traktowali sztukę abstrakcyjną członkowie Holenderskiej grupy De Stijl. Jak pisał Paul Owery: Wszyscy holederscy członkowie De Stijlu wywodzili się z rodzin kalwińskich. Pierwsze przykazanie: "Nie czyń sobie obrazu rytego...", kalwiniści interpretowali dosłownie. De Stijl przekształcił zakaz religijny zabraniający rzeźbienia wizerunków w zakaz estetyczny7. Rozpoznana przyroda pozwoli na tworzenie przyszłych mechanizmów samodzielnie. Jak pisał Mondrian w De Stijlu: W przyszłości człowiek będzie wybierał sobie własne otoczenie i będzie tworzył je sam. Dlatego też nie będzie odczuwał braku przyrody, jak niegdyś lud zmuszony do jej porzucenia /.../ Człowiek będzie budował miasta higieniczne i piękne dzięki wyważonemu skontrastowaniu budynków, konstrukcji i wolnych przestrzeni. A wtedy będzie tak samo szczęśliwy w domu jak i poza nim8. Tu, jako przykład, pokazujemy na rysunku 8. opracowaną przez Mondriana w serii obrazów konstrukcję, opartej na jabłoni, kompozycji abstrakcyjnej.

Gałęzie abstrakcyjnego drzewa

są jak ulice

ortogonalne

Fig. 8. Piet Mondrian. The flowering apple tree 1912-1921.

Rysunek 8. Piet Mondrian. Kwitnąca jabłoń. 1912-1921

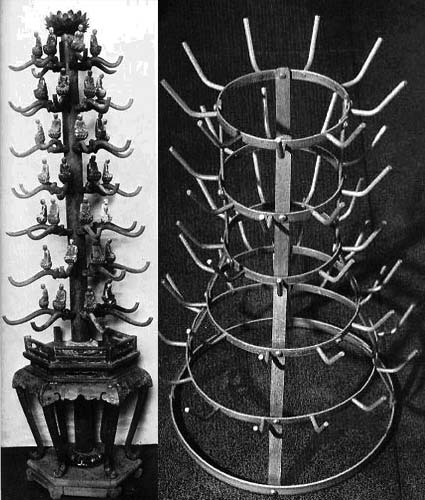

The recognition and use of an abstract backbone supposed to construct nature is not the only idea in our attitude to nature in the 20th century. According to Marcel Duchamp, we have not only the ability to discover meanings but also to transfer them. We give meanings to objects comparing their forms with images dormant within us. This way, we can discover an object - ready-made - in our surroundings. According to the Duchamp definition, a ready-made is an object of daily use elevated to the rank of an object of art by means of a simple decision of an artist. According to Krystyna Janicka, these objects: Frequently contained complicated allusions with many reference systems. For that reason, the creations of Duchamp are purely intellectual works9. Archetypes are not abstract creation, they exist in reality, they only have to be found around us as an oriental paradise that exists along with us and, if we purify our minds, we will enter it without effort. Figure 9 presents the archetypal Tree of Life found by Duchamp in the form of a bottle dryer.

If you find brilliants

listen to good advice

don't throw them away.

Rozpoznanie i wykorzystanie abstrakcyjnego szkieletu, który miał konstruować przyrodę, to nie jedyna idea naszej postawy wobec przyrody w XX wieku. Według Marcela Duchampa posiadamy nie tylko zdolność odkrywania, ale także przenoszenia znaczeń. My nadajemy znaczenie przedmiotom, porównując ich formę z drzemiącymi w nas obrazami. W ten sposób możemy odkryć w swoim otoczeniu przedmiot – Readymade. Według definicji Duchampa, ready-made to przedmiot codziennego użytku podniesiony do rangi dzieła sztuki prostą decyzją artysty. Według Krystyny Janickiej, te przedmioty: Często zawierały skomplikowane aluzje o wielu układach odniesienia. Z tej racji twórczość Duchampa jest tworem czysto intelektualnym.9 Archetypy nie są tworami abstrakcyjnymi, istnieją realnie, trzeba je tylko odnaleźć wokół siebie, jak orientalny raj, który obok nas istnieje i jeśli oczyścimy swój umysł, to bez trudu w niego wejdziemy. Na rysunku 9 możemy zobaczyć archetypowe Drzewo Życia odnalezione przez Duchampa w postaci suszarki na butelki.

Jeśli znajdziesz brylanty

posłuchaj dobrej rady

nie wyrzucaj ich.

Fig. 9. Buddha Tree with temple decoration, wood carving, China; Marcel Duchamp, Bottle Rack, 1914/1964. Readymade: bottle rack made of galvanized iron (Collection Diana Vierny), Roger Cook. 1972: The tree of life. Image for the Cosmos. Thames and Hudson, London

Rysunek 9. Drzewo Buddy - dekoracja świątyni, China; Marcel Duchamp, Suszarka do butelek, 1914/1964. Readymade: galwanizowana stal, (Kolekcja Diany Vierny) Roger Cook. 1972: The tree of life. Image for the Cosmos. Thames and Hudson, London

Contemporary art does not desire - as in early 20th century - the understanding of mechanisms shaping the nature; it believes that this is the path of science. It chooses empathy as the way to sink into the world of nature. Contemporary art is understood as the return to the roots of life - to the natural world - nature and not the artificial world - art10. Joseph Beuys, the author of the Avantgarde II, in his work: J like America and America likes Me (Fig. 10) stayed in the Denis Rene gallery in New York with a coyote for a few days. After a few days, he pushed him out of his lair. Man, in his art, should use not only his sapient soul. He should unite with the nature directly through the more primary souls existing in him: sen¬sual one and vegetative one. To unite with the world, in which these souls dominate: with the world of animals and the world of plants. Only then, he will feel his membership in the living world of nature.

Man - brother-werewolf.

Sztuka współczesna nie pragnie, tak jak wpoczątku XX wieku zrozumienia mechanizmów kształtujących przyrodę, uważa, że jest to droga nauki. Wybiera empatię jako drogę do wtopienia się w świat natury. Współcześnie sztuka jest rozumiana, jako powrót do korzeni życia – do świata naturalnego – natury, a nie do świata sztucznego - sztuki10. Joseph Beuys, twórca II Awangardy, w pracy: I like America and America likes Me (rysunek 10) przez kilka dni przebywał w Galerii Denis Rene w Nowym Jorku razem z kojotem. Po kilku dniach wypchnął go z jego legowiska. Człowiek w sztuce nie powinien posługiwać się tylko duszą rozumną. Powinien łączyć się z naturą bezpośrednio poprzez egzystujące w nim również pierwotniejsze dusze: zmysłową i wegetatywną. Łączyć ze światem, w którym te dusze dominują – ze światem zwierząt i ze światem roślin Dopiero wtedy odczuje swoją przynależność do żywego świata przyrody

Człowiek dla człowieka

wilkołakiem

Fig. 10. Joseph Beuys: I like America and America likes Me. Mai 1974. The Pack, 1969

Rysunek 10. Joseph Beuys: Ja lubię Ameryka a Ameryka lubi mnie, Mai 1974 ; The Pack, 1969

1. Mircea

Eliade 2002: Od Zalmoksisa do Czyngis-chana. PWN, Warsaw, p. 33.

2. (...) English gardens were arranged in line with ancient literary

toposes; their naturalness was skillfully directed and even made more

poetic thanks to artificial ruins; nevertheless, these "jardin parlants"

introduced new, intense contact with nature to the sentimentalism of

that time after: Krystyna Secomska 1991: Spor o starozytnosc. IS PAN,

Warsaw, p. 298.

3. Marcin

Fabiahski. 1994: Sztuka XVII wieku we Francji. [In:] Anna Lewicka

Morawska. Sztuka swiata. Tome 7. Wydawnictwo Arkady, Warsaw, p. 293.

4. Raffaela Russo 2002: Friedrich. Seria Geniusze malarstwa. Arkady,

Warsaw, p. 41.

5. Ibidem, p. 30-31.

6. That poem opens the introduction to the anthology - Michal Glowiriski

1991: Symbole i sym-bolika. Czytelnik, Warsaw, p. 5.

7. Paul Overy 1979: De Stijl, WAiF, Warsaw, p. 40.

8. Ibidem, s. 84

9.

Krystyna Janicka 1985: Surrealizm. Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe,

Warsaw, p. 168-170.

10. When conducting a performance we blur the difference between

art and reality, between what is artificial and what is natural. Jan

Swidzinski 2004: Introduction [in:] Miedzynarodowy festiwal sztuki

akcji. Galeria Off. Piotrkow Trybunalskl.

1. Mircea

Eliade 2002: Od Zalmoksisa do Czyngis-chana. PWN. Warszawa, s. 33

2. /.../ Według starożytnych toposów literackich komponowano w XVIII

wieku ogrody angielskie; ich naturalność była umiejętnie reżyserowana, a

nawet upoetyzowana przez sztuczne ruiny; tym niemniej, owe "jardin

parlants" wnosiły do ówczesnego sentymentalizmu nowy, intensywny kontakt

z przyrodą za Krystyna Secomska 1991: Spór o starożytność, IS PAN,

Warszawa, s. 298

3. Marcin Fabiański. 1994: Sztuka XVII wieku we Francji. [w:] Anna

Lewicka Morawska. Sztuka świata. tom 7. Wydawnictwo Arkady, Warszawa.

s.293

4. Raffaela Russo, 2002: Friedrich. Seria Geniusze malarstwa, Arkady,

Warszawa, s. 41

5. Ibidem, s. 30-31

6. Wiersz ten otwiera wstęp do antologii - Michał Głowiński 1991:

Symbole i symbolika, Czytelnik, Warszawa, s. 5

7. Paul Overy 1979: De Stijl, WAiF, Warszawa, s. 40

8. Ibidem, s. 84

9. Krystyna Janicka 1985,: Surrealizm, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne

i Filmowe, ss. 168-170.

10. Robiąc performance zacieramy różnice między sztuką a

rzeczywistością, między tym, co sztuczne a tym, co naturalne. Jan

Świdziński 2004: Wstęp [w:] Międzynarodowy festiwal sztuki akcji.

Galeria Off. Piotrków Trybunalski.